6th August 2013

The first time I’d really heard about the Bletchley Park Museum was last fall when Dr. Sue Black was interviewed by Aleks Krotoski on the Guardian Tech Weekly podcast, Sue Black on the campaign to save Bletchley Park. I mean, I probably heard about it in a high school world history class but that’s about twenty plus years ago.

I developed quite an interest in the restoration project and when I knew I was going to the UK, I decided that I was going to make a plan to visit the Museum. I checked with my cousin who was also interested in coming with me so I got us two return train tickets from Epsom to Bletchley Park. On the day of travel to Bletchley, the train from Epsom to Victoria Station was fine but apparently some idiot decided to jump onto the Victoria Line tube tracks during the 9am rush hour period so there was going to be a delay in service. After waiting a few minutes, we decided to take a taxi over to Euston Station to get our connecting National Rail train to Bletchley. The train to Bletchley was fairly relaxing as it was a north-based train off-peak time. The train station is pretty much across the street from the Museum grounds – just up the street a short distance away.

I did pick up a copy of the Bletchley Park Visitor’s Guide as I knew there was going to be so much information presented that I would never remember it all, and I have to admit that my understanding of the complexity of the mathematics coding that went into deciphering the messages is not anywhere near the level of knowledge involved. This is not a history lesson and I know there is plenty of information that will be inadvertedly left out. If you want to know more detailed information, there’s lots of wonderful books out available through the Bletchley Park Museum Store and Amazon.co.uk.

The strategic location for the codebreaking teams of scholars was chosen because it wasn’t in London but also not too far, accessible by train, and on major communications links connectors.

For anyone who doesn’t know, Bletchley Park was the site of the code breaking of the Enigma Code during World War II. The German military (Army, Navy and Air Force) used a more advanced Enigma Cipher machines during World War II to send messages to the field commanders and the High Command, and they consistently believed that throughout the war that these messages would not be able to be deciphered. During war time, the codes were changed daily, giving 159 million million million possible settings to choose from. The Polish initially broke the code in 1932 with intermittent trials, but the Germans had advanced the machines for their military use during wartime. Knowing they were going to be imminently invaded by the Germans, the Polish informed the British in 1939, when they needed help to break the newer designed Enigma cipher machines. The initial break of the German enigma machines came in 1940 under the team lead by Dilly Knox, with the mathematicians John Jeffreys, Peter Twinn and Alan Turing, unravelled the German Army administrative key that became known at Bletchley Park as ‘The Green’ (source: Breaking Enigma).

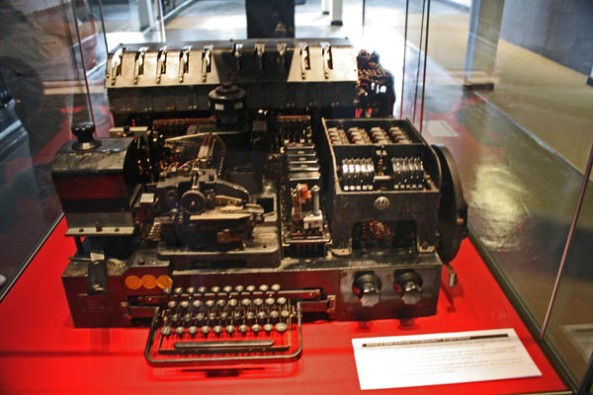

To look at the Engima Cipher machines, there is a typewriter-like Qwerty board (without the symbols). Above those typewriter keys is a panel of three rows with corresponding qwerty buttons. In addition, under the front panel of the Enigma machines was another row of corresponding keys with wires running to different outputs, so one letter would represent another, but not the same letter twice in a row turned up even if you pressed the same letter on the keyboard. The machine’s elements can lead to billions of permutations of possible outcomes. Both the Enigma machine and the deciphering machine had to be set up the exact same way in order to send and receive messages. In addition to figuring out the Enigma coding, the British used an encryption device called the Typex, that was an adaptation of the Enigma machine, with enhancements that increased security.

Enigma Cypher Machine, Bletchley Park Museum, Milton-Keynes, UK. © J. Lynn Stapleton, 6th August 2013

This video more easily explains what I was trying to say:

The number of possible permutations was pretty astronomical to be done by hand so British mathemeticians Alan Turing and Gordon Welchman built on the information provided by the Poles and were able to build the Bombe machine that would enable them to more easily decipher the German messages. Once it was determined which letter represented another letter, the mathematicians would look for repeating patterns of words, some found in error. As you can see in the photo below of the Bombe machine, there are three banks of dials, stacked three high in each bank, and 12 rows of dials. Each row of three represented one Enigma machine that would go through the possible choices, and each Bombe machine represented 36 Enigma machines. As the top one rotated so many times, the next one below would move one stop, and once the middle one rotated one full stop the bottom dial would start to turn, until each locked in one letter combination, that was then checked on another machine. The Bombe machines brought the number of possible permutations down to a level where they could be checked by hand and then checked through an interpreter who knew the German language. It was rather fascinating to watch them go through the process with the Turing Bombe Rebuild Project machine. For further information, please visit: Bombe Rebuild Project. Below the image is another video, properly explaining the process of deciphering Enigma with the Bombe machines and working out how letters possibly worked together to form words and messages.

The Turing Bombe Rebuild Project, Bletchley Park Museum, Milton-Keynes, UK © J. Lynn Stapleton, 6th August 2013

In the video, you can kind of get an example of how loud these Bombe machines were. Two huts (Huts 11 and 11A) housed the Bombe machines and contained several rows on either side of the huts, and they were operated by the Women’s Royal Navy Service (WRNS) – nicknamed Wrens. There were also Bombe machines were produced and operated in Eastecote and Stanmore on the outskirts of London, and a few in the US, but Hut 11A was the main control centre for all Bombe machines in the UK. The huts were stated to be hot and noisy as there was poor ventilation and no accessible windows. Hut 11 is currently open to the public and Hut 11A is currently being restored and will open this autumn.

Not only did the mathemeticians work on deciphering the Enigma machines, but they also worked to decipher the coding of the Lorenz machines used by Hitler, the High Command and German Army commands throughout occupied Europe. The operator transmitted a clear twelve-letter indicator which told the receiving operator the exact rotor start positions. He entered all the 4000 characters only to be told by the receiving operator that he hadn’t got it. Assuming the system was unbreakable, the operator used the same settings and because it was standard procedure, sent the indicator again. Therein lay his mistake. He compounded the error by using abbreviations when he re-keyed the message, because the small differences were a great help to crypanalyst John Tiltman. It took Tiltman ten days but he recovered both German messages in full, thanks to the operator’s mistake.

As the Lorenz was more complicated than Enigma, to encrypt by hand was almost impossible. The British first developed an initial attempt called the Newmanry after Dr. Max Newman, but then they called on Post Office Engineer Tommy Flowers who designed the Colossus machine – that would read paper tape at 5000 characters per second. The Colossus machine would be the forerunner of today’s computers.

Another cypher machine that was used was the Siemens & Halske T52 Schlüsselfernschreibmaschine (SFM), codenamed Sturgeon by British cryptanalysists. The T52 was used by the German Naval units due to their weight, while the Army units used the Lorenz. The Bletchley Park Museum has a couple of these for viewing.

Lorenz Schlusselzusatz Cypher machine, Bletchley Park Museum, Milton-Keynes, UK. © J. Lynn Stapleton, 6th August 2013

“Sturgeon” Cypher Machine. Bletchley Park Museum, Milton-Keynes, UK. © J. Lynn Stapleton, 6th August 2013

The Museum site is quite a large-sized area encompassing numerous blocks and huts that contained the various military and civilian divisions. Several of these huts worked as teams in order to more quickly process the encoded and deciphered information, sending it through translation and analysis, building up cards of information of people and places that were revealed and then relayed to the Command Centre in the mansion. One of the methods of transferring that information on the Park grounds was by motorcycle, such as the one below.

In 1992 the Bletchley Park Trust was set up to preserve the historic buildings, and has managed to save it and develop the site as museum with a wonderful educational program. The restoration of the site to its WWII era appearance will take about ten years and £20 million. The first phase of the project fundraising was completed at £7.4 million.

Inside Block B contains the largest collection of Enigma machines on public display. It also contains a large section on the contributions of Alan Turing to Bletchley Park and to the history of modern computer programming. During WWII, Turing worked for the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley. The display includes old diaries, an old teddy bear, a detailed history of his accomplishments and his posthumous pardon, and an artfully sculpted slate statue of Alan Turing done by Stephen Kettle.

Slate statue of Alan Turing by Stephen Kettle, Bletchley Park Museum, Milton-Keynes, UK. © J. Lynn Stapleton, 6th August 2013

Alan Turing Teddy Bear, Bletchley Park Museum, Milton-Keynes, UK. © J. Lynn Stapleton, 6th August 2013

Over the span of World War II, the contributions of those working at Bletchley Park led to:

- Location of the U-Boat packs in the Battle of the Atlantic

- Identifying the beam guidance system for German bombers

- The Mediterranean and North African campaigns, including El Alamein

- Launch and success of Operation Overlord, including breaking German Secret Service Enigma, complementing the Double Cross operation which misled Germany on the intended target for D-Day

- Helping to identify new weapons including German V weapons, jet aircraft, atomic research and new U-Boats

- Analysts of the effect of the war on the German economy

- Breaking Japanese codes

- The outcome of the war in the Pacific.In addition to the images shown above, I was able to take a number of photographs around the complex campus of the museum grounds.

On the grounds there is this wonderful monument to the Polish mathematicians who’s assistance to Bletchley Park’s work during WWII was instrumental in helping win the war. Upon the monument is etched the following words (both in English and Polish – but for here, I’ll just type out the English).

“This plaque commemorates the work of Marian Rejewski, Jerzy Rozyckland, Henry K. Zygalski – mathematicians of the Polish Intelligence NCE Service in first breaking the Enigma code. Their work greatly assisted the Bletchley Park Code Breakers and contributed to the Allied victory in World War II.”

These are some of the vehicles in the Park’s garages.

As we were leaving the Museum for the day, I was endlessly fascinated by the whole visit, but there was so much information to take in that I knew I wouldn’t remember it all, without reference to look back on. We headed back to the train station to wait for our train, which due to troubles on the line north of where our station was, we were delayed about an hour and a bit. Occasionally we’d just sit and wait as the Virgin Rail high speed trains went whizzing by (going from London to Manchester). We nicknamed it ‘The Virgin Bullet’. The first shot I took was a big blur, but putting it over to the automatic setting for Action, I did get a good shot of the train as it went through the station stop:

If you’ve never been to the Bletchley Park Museum, I highly recommend it. It is truly spectacular and will continue to be as it goes through its restoration process. It’s an absolutely stunning outing to explore. Check Opening Times for visiting information. Bletchley Park is open to visitors daily except 24, 25, 26 December and 1 January.

____________

Information for this post was provided by the Bletchley Park Museum website and the Bletchley Park: Home of the Codebreakers Guidebook, as well as YouTube for the video links.